5. Special Medical Considerations in FOP

-

5-5. Cardiopulmonary Function in FOP

5-6. Respiratory Health in FOP

5-7. Immunizations in FOP for Diseases Other Than Influenza and Covid-19

5-8. Immunizations for Influenza in FOP

5-9. Coronavirus (COVID-19) Precautions & Guidance for FOP Patients & Families

5-10. Acute & Chronic Pain Management in FOP

5-11. Neurological Issues in FOP

5-12. Developmental Arthropathy and Degenerative Joint Disease in FOP

5-13. Differential Diagnosis of Hip Pain in FOP

5-19. Temporomandibular Subluxations in FOP

5-20. Nutrition, Calcium & Vitamin D Guidelines in FOP

5-21. Preventive Oral Healthcare in FOP

5-22. Extraction of Wisdom Teeth

5-24. Submandibular Flare-ups in FOP

5-26. Dental Anesthesia in FOP

5-27. General Anesthesia in FOP

5-28. Acceptable/Low Risk Procedures in FOP

5-29. Hearing Impairment in FOP

5-30. Gastrointestinal Issues in FOP

5-32. Rehabilitation Issues in FOP

5-33. Aids, Assistive Devices, and Adaptations (AADAs)

5-1. Introduction

Individuals who have FOP can also develop common problems (gall bladder disease, appendicitis, colds, earaches, etc.) as with anyone in the general population. Generally, the safest way to diagnose and treat these problems in a patient with FOP is to ask the question: “How would I evaluate this patient if he or she did not have FOP?” Following that, the “FOP filter” can be applied to ask: “Given the nature of the possible intercurrent medical problem, and the relative risks that particular problem presents in relation to FOP, are there any diagnostic or treatment procedures that should or should not be undertaken (or perhaps alternative diagnostic procedures might be more appropriate)?” Using that approach, diagnostic dilemmas can often be resolved, and appropriate care delivered. When questions remain, experts on FOP should be consulted (Kaplan et al., 2018; see Section 12 – Authors’ Contact Information).

In addition to common medical problems that individuals with FOP might have, there are a number of special medical considerations for FOP patients that are worthy of very special attention. They are presented below.

5-2. Injury Prevention in FOP

Prevention of soft-tissue injury and muscle damage remain a hallmark of FOP management. Intramuscular injections must be avoided. Routine childhood diphtheria-tetanus-pertussis immunizations administered by intramuscular injection pose a substantial risk of permanent heterotopic ossification (HO), as do arterial punctures whereas measles-mumps-rubella immunizations administered by subcutaneous injection and routine venipuncture pose little risk (Lanchoney et al., 1995). Biopsies of FOP lesions are never indicated and will likely cause additional HO. Elective amputations are never indicated.

Permanent ankylosis of the jaw may be precipitated by minimal soft tissue trauma during routine dental care. Assiduous precautions are necessary in administering dental care to anyone who has FOP. Overstretching of the jaw and intramuscular injections of local anesthetic must be avoided. Mandibular blocks cause muscle trauma that will lead to HO, and local anesthetic drugs are extremely toxic to skeletal muscle (Luchetti et al., 1996).

Falls suffered by FOP patients can lead to severe injuries and flare-ups. Patients with FOP have a self- perpetuating fall cycle. Minor soft tissue trauma often leads to severe exacerbations of FOP, which result in HO and joint ankylosis. Mobility restriction from joint ankylosis severely impairs balancing mechanisms, and causes instability, resulting in more falls (Glaser et al., 1998).

Falls in the FOP population are more likely to result in severe head injuries, loss of consciousness, concussions, and neck and back injuries, compared to people who do not have FOP. Individuals with FOP are often unable to use the upper limbs to absorb the impact of a fall. FOP patients are much more likely to be admitted to a hospital following a fall and have a permanent change in physical function because of the fall. In a group of 135 FOP patients, 67% of the reported falls resulted in a flare-up of the FOP. Use of a helmet by young patients may help reduce the frequency of severe head injuries that can result from falls (Glaser et al., 1998).

Measures to prevent falls should be directed at modification of activity, improvement in household safety, use of ambulatory devices (such as a cane, if possible), and use of protective headgear. Redirection of activity to less physically interactive play may also be helpful. Complete avoidance of high-risk circumstances may reduce falls, but also may compromise a patient’s functional level and independence and may be unacceptable to many. Adjustments to the living environment to reduce the number of falls within the home may include installing supportive hand-railings on stairs, securing loose carpeting, removing objects from walkways, and eliminating uneven flooring including doorframe thresholds. Prevention of falls due to imbalance begins with stabilization of gait. The use of a cane or stabilizing device may improve balance for many patients. For more mobile individuals, the use of a rolling cane or a walker will assist in stabilization.

When a fall occurs, prompt medical attention should be sought, especially when a head or neck injury is suspected. Any head or neck injury should be considered serious until proven otherwise. A few common signs and symptoms of severe head injury include increasing headache, dizziness, drowsiness, obtundation, weakness, confusion, or loss of consciousness. These symptoms often do not appear until hours after an injury. An FOP patient should be examined carefully by a healthcare professional if a head or neck injury is suspected.

As mentioned previously, prednisone use should be considered prophylactically following major soft tissue trauma, or peri-operatively. The dose of corticosteroids is dependent upon body weight. A typical dose of prednisone is 1-2 mg/kg/day (up to 100 mg), administered as a single daily dose for no more than 4 days (Table 1). In order to have the least suppressive effect on the hypothalamic-pituitary-adrenal axis, medication should be taken in the morning.

References

Glaser DL, Rocke DM, Kaplan FS. Catastrophic falls in patients who have fibrodysplasia ossificans progressiva. Clin Orthop 346: 110-116, 1998

Lanchoney TF, Cohen RB, Rocke DM, Zasloff MA, Kaplan FS. Permanent heterotopic ossification at the injection site after diphtheria-tetanus-pertussis immunizations in children who have fibrodysplasia ossificans progressiva. J Pediatrics 126: 762-764, 1995

Luchetti W, Cohen RB, Hahn GV, Rocke DM, Helpin M, Zasloff M, Kaplan FS. Severe restriction in jaw movement after route injection of local anesthetic in patients who have fibrodysplasia ossificans progressiva. Oral Surg Oral Med Oral Pathol Oral Radiol Endod 81: 21-25, 1996

5-3. Scalp Nodules in FOP

Scalp nodules are flare-ups on the head, commonly appearing in childhood – often the first post-natal manifestations of FOP. Scalp nodules are of little clinical significance despite their often large size and alarming appearance.

Scalp nodules are noted in very few publications (Kitterman et al., 2005; Piram et al., 2011; Kardile et al., 2012; Al Kaissi et al., 2016). They are often reported as first symptom of FOP, from the neonatal period (about 10% of cases (Kitterman et al., 2005), but also may be an under-recognized symptom at any age. The median age of onset is 1.5 years (Piram et al., 2011).

Clinically, scalp nodules may be solitary or numerous, immobile, with a variable size, from a walnut size to a great volume such as a tennis ball. They may be asymptomatic or painful only at onset. Usually, they appear and regress spontaneously, or can develop after trauma or infection, or in a child who is apparently in good health.

Radiographs are unnecessary but generally show soft tissue thickening initially with small zones of HO after some months. Biopsies/surgical excision or fine-needle aspiration for cytological and histologic studies must be avoided. Histopathologic findings are described in three patients by Piram et al., 2011 as proliferation of short spindle-shaped cells in the deep subcutaneous tissue, with abundant collagenous stroma and scattered inflammatory cells (mast cells & T-cells) and numerous vessels.

The correlation between their presence and the genotype is not detailed in the few reported cases but it appears that they are associated with the R206H classic mutation in ACVR1 in numerous cases studied.

The occurrence of unique or multiple scalp nodule(s) in infancy is an important early sign of FOP and may be the first sign of a post-natal flare-up of the condition. The presence of scalp nodules during infancy should prompt immediate examination of the great toes – a clinical scenario that could appropriately accelerate the proper diagnosis of FOP.

So, importantly, when scalp nodules are seen, the toes must be examined! Even more importantly, biopsies must not be performed. Symptomatic treatments may be prescribed but steroids are not used as no joints are involved. Despite their often alarming appearance, no treatment is necessary. Swelling subsides with time – and if ossification occurs, remodeling is common as the lesions are incorporated into the growing skull.

References

Al Kaissi A, Kenis V, Ben Ghachem M, Hofstaetter J, Grill F, Ganger R, Kircher SG. The diversity of the clinical phenotypes in patients with fibrodysplasia ossificans progressiva. J Clin Med Res 8: 246-253, 2016

Kitterman JA, Kantanie S, Rocke DM, Kaplan FS. Iatrogenic harm caused by diagnosis errors in FOP. Pediatrics 116: 654-661, 2005

Kardile M, Nayak S, Nagaraja HS, Mishra AK. Fibrodysplasia ossificans progressiva in a four-year-old child. J Orthop Case Rep 2: 17-20, 2012

Piram M, Le Merrer M, Bughin V, De Prost Y, Fraitag S, Bodemer C. Scalp nodules as a presenting sign of fibrodysplasia ossificans progressiva: a register-based study. J Am Acad Dermatol 64: 97-101, 2011

5-4. Spinal Deformity in FOP

Spinal deformities are common in individuals who have FOP. A study in 40 FOP patients showed that 65% had radiographic evidence of scoliosis. The initial clinical abnormality was a rapidly developing scoliosis associated with a spontaneously occurring lesion in the paravertebral soft tissues. Once established, these deformities lead to rapid, permanent loss of mobility and to progressive spinal deformity with growth (Shah et al., 1994).

The formation of a unilateral osseous bridge along the spine prior to skeletal maturity limits growth on the ipsilateral side of the spine while growth continues uninhibited on the contralateral side. If an osseous bridge occurs bilaterally and the two bridges are relatively symmetrical, or if an osseous bridge forms after skeletal maturity, scoliosis will not result.

Severe scoliosis in FOP can lead to pelvic obliquity, similar to that seen in scoliosis resulting from other causes, and the obliquity can impair the balance of the trunk as well as standing and/or sitting balance.

Anecdotal experience in five patients suggests that traditional operative approaches to scoliosis in FOP patients can seriously exacerbate the disease. Furthermore, three patients in the series who had operative correction of the scoliosis continued to have progression of the spinal curve even after a spinal arthrodesis. In two of these patients, the arthrodesis was performed posteriorly and not anteriorly. Thus, continued anterior growth of the spine exacerbated rotational deformity.

Indications for correction of spinal deformity associated with more usual types of scoliosis do not pertain to patients with FOP. With the limited knowledge available, the risks of severe complications (most notably, the exacerbation of HO at sites remote from the operative field) that are associated with correction of spinal deformity in FOP likely outweigh the benefits (Shah et al., 1994). However, with greater knowledge of the natural history of FOP and newer surgical techniques, these old assertions are undergoing careful re-examination on a case-by-case basis.

A study of three patients with rapidly evolving chin-on-chest deformities suggests that a more aggressive surgical approach may be necessary to prevent and/or correct such rapidly progressive deformities in patients who have FOP (Moore et al., 2009).

References

Moore R, Dormans J, Drummond DS, Shore EM, Kaplan FS, Auerbach J. Chin-on-chest deformity in patients who have fibrodysplasia ossificans progressiva (FOP). J Bone Joint Surg Am 91: 1497-1502, 2009

Shah P, Zasloff MA, Drummond, D, Kaplan FS. Spinal deformity in patients who have FOP. J Bone Joint Surg Am 76: 1442-1450, 1994

5-5. Cardiopulmonary Function in FOP

A recent natural history study showed that individuals with ACVR1R206H mutations have an increased prevalence of cardiac conduction abnormalities on electrocardiogram. Conduction abnormalities were present in 45.3% of baseline ECGs, with the majority of abnormalities classified as nonspecific intraventricular conduction delay (37.7%). More specifically, 22.2% of patients > 18 years old had conduction abnormalities, which was significantly higher than a prior published study of a healthy population (5.9%; n = 3978) (p < 0.00001). Patients with FOP < 18 years old also had a high prevalence of conduction abnormalities (62.3%). The 12-month follow up data was similar to baseline results. Conduction abnormalities did not correlate with chest wall deformities, scoliosis, pulmonary function test results, or increased Cumulative Analog Joint Involvement Scale (CAJIS) scores. Echocardiograms from 22 patients with FOP revealed eight with structural cardiac abnormalities, only one of which correlated with a conduction abnormality (Kou et al., 2020).

In summary, individuals with FOP may have subclinical conduction abnormalities manifesting on ECG, independent of heterotopic ossification. Although clinically significant heart disease is not typically associated with FOP, and the clinical implications for cardiovascular risk remain unclear, knowledge about ECG and echocardiogram changes is important for clinical care and research trials in patients with FOP. Further studies on how ACVR1/ALK2R206H affects cardiac health will help elucidate the underlying mechanism (Kou et al., 2020).

Patients with FOP develop thoracic insufficiency syndrome (TIS) that can lead to life-threatening complications. Features contributing to TIS in patients with FOP include:

Costovertebral malformations with orthotopic ankylosis of the costovertebral joints

Ossification of intercostal muscles, paravertebral muscles and aponeuroses

Progressive spinal deformity including kyphoscoliosis or thoracic lordosis

Pneumonia, hypoxemia, hypercarbia, pulmonary hypertension and right-sided heart failure are the major life-threatening hazards that result from TIS in patients with FOP. Prophylactic measures to maximize pulmonary function, minimize respiratory compromise, and prevent influenza and pneumonia are helpful in decreasing the morbidity and mortality from TIS in patients with FOP (Kussmaul et al., 1998; Kaplan & Glaser, 2005; Kaplan et al., 2010). A pulmonologist should be involved early with regular spirometry assessments and sleep studies as needed.

Individuals with FOP develop progressive limitations in chest expansion, resulting in restrictive lung disease, with reduced vital capacity but no obstruction to air flow. Those with advanced disease have extremely limited chest expansion and rely on the diaphragm for inspiration (Kussmaul et al., 1998). The low inspiratory capacity results in low expiratory flow rates, in many cases.

Consequently, individuals with FOP are subject to atelectasis, retained secretions, hypoxemia, hypercarbia and pneumonia. All patients had abnormal spirometry secondary to TIS. Chest infection in the presence of diminished pulmonary reserve is the major hazard to life in patients with FOP. Many patients had abnormal electrocardiograms, with evidence of right ventricular dysfunction. It is suggested that the presence of severe restrictive disease of the chest wall is associated with a high incidence of right ventricular abnormalities (Kaplan et al., 2010).

Respiratory failure and cor pulmonale are features of severe TIS (Shah et al., 1974). A detailed description of this problem (Bergofsky et al., 1979) noted right ventricular hypertrophy in at least 10% of cases.

Pulmonary hypertension was a common finding, which these authors attributed to increased vascular resistance and the effects of prolonged alveolar hypoventilation.

The respiratory problems seen in patients with FOP are similar to those seen in patients with respiratory muscle weakness such as cervical spinal cord injury, or other skeletal abnormalities such as kyphoscoliosis. Strategies similar to those used in these other populations to maximize respiratory muscle functional and clear secretions may be beneficial in those with FOP.

Inspiratory and expiratory muscle training should be routinely practiced and started at the age of diagnosis. A variety of incentive spirometers are available to encourage deep breathing. Inspiratory muscle training devices permit progressive resistance exercise training of the diaphragm.

Careful attention should be directed toward the prevention and therapy of intercurrent chest infections. Such measures should include prophylactic pneumococcal pneumonia and influenza vaccinations (given subcutaneously), chest physiotherapy, and prompt antibiotic treatment of early chest infection.

Upper abdominal surgery should be avoided, if possible as it interferes with diaphragmatic respiration. Sleep studies to assess sleep apnea may be helpful. Positive pressure assisted breathing devices such as BiPAP® (Bi-level positive airway pressure) masks without the use of supplemental oxygen may also be helpful. Night CPAP and noninvasive ventilation on ambient air may be effective treatments for nocturnal hypoventilation/hypoxemia.

Patients with FOP who have advanced TIS and who use unmonitored oxygen have a high risk of sudden death. Sudden correction of oxygen tension in the presence of chronic carbon dioxide retention suppresses respiratory drive. Patients who have FOP and severe TIS should not use supplemental oxygen in an unmonitored setting (Kaplan & Glaser, 2005; Kaplan et al., 2010).

During hospitalizations or in more advanced disease, individuals with FOP may have trouble clearing secretions. This can lead to atelectasis, pneumonia and respiratory failure requiring endotracheal intubation. Secretion clearance is enhanced by adequate hydration, guaifenesin, bronchodilators and mucolytics, as needed. If endotracheal intubation or a surgical procedure are considered, nasal fiberoptic intubation of the trachea is recommended (Kilmartin et al. 2014). For surgical or interventional procedures, a carefully designed anesthesia plan is paramount. Planning for extubation of the trachea should be weighed against creation of tracheostomy if impending respiratory failure is expected due to the advanced TIS. Postoperative care should be assigned to an intensive care setting.

There is also much that can be done in prevention. Individuals with FOP are often born with congenital malformations of the costovertebral joints that cause some degree of chest restriction even before the appearance of heterotopic bone, although these restrictions may not lead to any clinical problems early in life. However, because of these restrictions, individuals with FOP are more likely to rely, even early in life, on diaphragmatic breathing. It is recommended that individuals with FOP be evaluated by a pulmonologist by the end of the first decade of life in order to perform baseline pulmonary function tests and echocardiograms. The results of these tests may further help guide preventative care for the cardiopulmonary system.

Several devices are available to loosen secretions from relatively simple handheld devices that cause vibration of the airway walls during exhalation, to garments that vibrate the chest wall to high technology specialty beds that turn and oscillate. Care must be taken when using such devices in patients with a weak cough, as they may be unable to expectorate the secretions once loosened. Use of mechanical insufflation-exsufflation can non-invasively extract retained secretions from individuals with ineffective cough. The device can dramatically increase peak cough expiratory flow in individuals with impaired expiratory muscle function. Combining a method to loosen secretions with in-exsufflation to remove them may prevent respiratory failure and the need for mechanical ventilation. However, all percussive devices should be used with caution due to risk of inducing trauma.

Various activities can help maximize the strength of the diaphragm and perhaps decrease the risk of intercurrent pulmonary problems. In addition to the intermittent use of incentive spirometry, other activities such as deep breathing, swimming/hydrotherapy, and singing, should be encouraged at an early age and may help improve long-term pulmonary function.

Pulmonary hypertension (PH) is a complication of TIS which is a common feature of FOP. Early symptoms are non-specific and include dyspnea on exertion and fatigue. In FOP, a high index of suspicion is warranted if severe restrictive lung disease or moderate disease exists over a prolonged period of time. If PH is suspected transthoracic echocardiography should be performed, since it permits a noninvasive estimation of pulmonary arterial systolic pressure (usually > 25 mm Hg in PH) and evaluation of both right and left heart size and function. Although right heart catheterization confirms the diagnosis of PH, it can reasonably be deferred in FOP in the setting of known severe restrictive lung disease or other proximal causes such as advanced left-sided heart disease or chronic hypoxia. When possible, treatment of the underlying condition is the primary goal of management for PH; however, in FOP, PH is most commonly associated with restrictive lung disease which is not easily treated due to immobility of the chest cavity. Therefore, in FOP, therapy for PH is directed at PH itself and is best managed by pulmonologists.

Anecdotal evidence exists for the use of phosphodiesterase-5 inhibitors such as sildenafil or tadalafil, and should be considered as an initial oral therapy for mild to moderate PH.

References

Bergofsky EH. Respiratory failure in disorders of the thoracic cage. Am Rev Resp Dis 119: 643–669, 1979

Kaplan FS, Glaser DL. Thoracic insufficiency syndrome in patients with fibrodysplasia ossificans progressiva. Clin Rev Bone Miner Metab 3: 213-216, 2005

Kaplan FS, Zasloff MA, Kitterman JA. Shore EM, Hong CC, Rocke DM. Early mortality and cardiorespiratory failure in patients with fibrodysplasia ossificans progressiva. J Bone Joint Surg Am 92: 686-691, 2010

Kilmartin, E, Grunwald, Z, Kaplan FS, Nussbaum BL. General anesthesia for dental procedures in patients with fibrodysplasia ossificans progressiva: A review of 42 cases in 30 patients. Anesth Analg 118: 298- 301, 2014

Kou S, De Cunto C, Baujat G, Wentworth KL, Grogan DR, Brown MA, Di Rocco M, Keen R, Al Mukaddam M, le Quan Sang KH, Masharani U, Kaplan FS, Pignolo RJ, Hsiao EC. Patients with ACVR1(R206H) mutations have an increased prevalence of cardiac conduction abnormalities on electrocardiogram in a natural history study of fibrodysplasia ossificans progressiva. Orphanet J Rare Dis 2020 Jul 29;15(1):193

Kussmaul WG, Esmail AN, Sagar Y, Ross J, Gregory S, Kaplan FS. Pulmonary and cardiac function in advanced fibrodysplasia ossificans progressiva. Clin Orthop 346: 104-109, 1998

Shah PB, Zasloff MA, Drummond D, Kaplan FS. Spinal deformity in patients who have fibrodysplasia ossificans progressiva. J Bone Joint Surg Am 76: 1442–1450, 1994

5-6. Respiratory Health in FOP

Strong respiratory health is important for everyone. This is particularly true for individuals with FOP since FOP can severely decrease respiratory capacity from the chest wall deformities, heterotopic ossification and scoliosis (Shah et al.,1994; Towler et al., 2020; Botman et al, 2021).

Maintaining strong respiratory health involves a few things:

Infection precautions, particularly during the flu season: Make sure that all FOP patients and their family members wash their hands regularly and use alcohol gel. Avoid places where infection can be easily transmitted. In the event that exposures need to occur, we recommend that individuals with FOP wear a simple surgical mask to decrease the risk of breathing in infected droplets (such as from a sneeze). These masks are not meant to filter out all viruses and infectious bacteria but will balance the need to decrease exposure to larger droplets with comfortable breathing. Alternatively, a high quality N95 or KN95 mask can be very effective in decreasing exposure.

Maintaining respiratory capacity: We recommend 15-30 minutes per day of active respiratory activity. This should not be uncomfortable or cause pain but is meant to help keep the diaphragm and other respiratory muscles healthy. Activities that we recommend include vigorous vocalizations (i.e. singing, as in a choir; loud continuous vocal activity like singing in the shower), blowing bubbles, etc.

For some, an incentive spirometer can complement vigorous vocalizations. These devices can be used to measure lung capacity. However, we recommend using them as a way to maintain lung capacity and make sure the lungs are well-ventilated.

FOP patients who decide to have yearly influenza immunizations should use the subcutaneous immunization, given by an experienced provider. The flu immunization should not be given during a flare- up and not until at least 2 weeks after a flare-up has resolved. Whether or not the FOP patient decides to get a flu vaccine, all immediate family members, household contacts and caretakers should be immunized.

In the case where the flu vaccine is not obtained, for whatever reason, having a ready supply of Oseltamivir (Tamiflu) on hand during flu season is a reasonable precaution. At the first signs of the flu (fever or feeling feverish/chills, cough, sore throat, runny or stuffy nose, muscle or body aches, headaches, fatigue (tiredness), vomiting and diarrhea), one should take the first dose of Oseltamivir and then immediately contact their physician (Jefferson et al., 2014).

Patients should also consider vaccines for other respiratory illnesses, including pneumococcus and COVID-19. See the respective sections for additional details.

There are many types of incentive spirometers available and many different strategies for maintaining lung function. The IFOPA provides two types depending on age and jaw needs.

Peak Flow Whistle (for young children)

For young children, a peak flow whistle is recommended. These whistles will make a sound when air is blown fast enough through the whistle. The most important part of this device is taking the deep breath beforehand – not the actual ability to generate the whistle sound!

The patient should:

Sit upright or stand.

Place the whistle in the mouth, and make sure the lips are tightly sealed

Slowly inhale as much as possible (this is the most important part). Hold the breath for about 10 seconds.

Exhale quickly through the whistle to generate the sound.

Rest in between breaths.

Repeat 10 times, with short rest breaks in between.

The patient should stop if they feel dizzy at any time, or if they have any tenderness or chest discomfort.

The whistle should be set based on the patient’s estimated peak flow on a regular day (i.e. should just be able to whistle). Standard tables with FEV1 values are not useful in FOP due to the presence of chest deformities; however, prior PFT values can serve as a guide. The goal is to encourage deep breaths to minimize atelectasis, rather than increasing peak flow. The flow whistle serves as an incentive for children.

Incentive Spirometer

The incentive spirometer is for older children and adults. There are many models available. The goal, however, is the same with all the models - to take slow, deep breaths to expand the lungs.

The patient should:

Sit upright in a chair or bed or stand upright.

Hold the spirometer in front of the face at eye level. Many FOP patients will not be able to do this due to ankylosis of the joints in the upper extremities. They may need assistance or have the spirometer positioned close enough to use but without having to hold with both hands.

Close your lips around the mouthpiece to make a seal.

Slowly exhale completely.

Slowly inhale thorough the mouth as deeply as possible.

The piston will rise with inhalation.

Hold the breath for 10 seconds (the piston may fall during this time), then exhale.

Repeat 10 times, with short rest breaks in between.

Stop and rest if they feel dizzy at any time.

Perform this routine twice daily.

References

Botman E, Smilde BJ, Hoebink M, Treurniet S, Raijmakers P, Kamp O, Teunissen BP, Bökenkamp A, Jak P, Lammertsma AA, van den Aardweg JG, Boonstra A, Eekhoff EMW. Deterioration of pulmonary function: An early complication in Fibrodysplasia Ossificans Progressiva. Bone Rep 2021 Feb 25;14:100758

Jefferson T, Jones MA, Doshi P, Del Mar CB, Hama R, Thompson MJ, Spencer EA, Onakpoya I, Mahtani KR, Nunan D, Howick J, Heneghan CJ. Neuraminidase inhibitors for preventing and treating influenza in healthy adults and children. Cochrane Database Syst Rev 2014 Apr 10;(4)

Shah PB, Zasloff MA, Drummond D, Kaplan FS. Spinal deformity in patients who have fibrodysplasia ossificans progressiva. J Bone Joint Surg 76-A: 1442-1450, 1994

Towler OW, Shore EM, Kaplan FS. Skeletal malformations and developmental arthropathy in individuals who have fibrodysplasia ossificans progressiva. Bone 2020 Jan;130:115116.

5-7. Immunizations in FOP for Diseases Other Than Influenza and Covid-19

Vaccines against various infectious diseases have dramatically decreased morbidity and mortality from infectious diseases (Roush et al., 2007). Because individuals with FOP are subject to the same infectious diseases as the general population, immunizations are essential in FOP. However, there are several major considerations and precautions regarding immunization of those with FOP, and these are discussed below.

The Advisory Committee on Immunization Practices (ACIP) of the Center for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC) has published charts with their recommendations for immunization for children, adolescents, and adults. The chart for children and adolescents can be found at: https://www.cdc.gov/vaccines/schedules/hcp/imz/child-adolescent.html

The chart for adults is at: https://www.cdc.gov/vaccines/schedules/hcp/imz/adult.html

In addition, these sites contain a wealth of other information about immunizations including Parent Friendly Immunization Charts, Resources for Parents, Resources for Adults, Resources for Health Professionals, Vaccine Information Statements, and up to date clinical information about Covid-19 vaccines. Hard copies of the Immunization Charts can be obtained for free using these sites.

Those immunization recommendations, last updated in February 2023, have been approved by the American Academy of Pediatrics, the American Academy of Family Practitioners, and the American College of Obstetricians and Gynecologists.

For most of the vaccines given in childhood, the ACIP recommends intramuscular (IM) administration. However, IM injections are contraindicated in FOP because of the risk of heterotopic ossification (HO) at the injection site and sometimes elsewhere in the body. Lanchoney and associates reported that IM injection of diphtheria-pertussis-tetanus (DPT) vaccines caused flare-ups and subsequent HO in 27% of children with FOP and, in some cases, permanent loss of joint motion (Lanchoney et al., 1995).

Furthermore, subcutaneous (SubQ) injection of DPT type vaccines may also cause flare-ups, HO and loss of joint mobility (F. Kaplan, personal communication). Therefore, it seems that some unidentified component(s) of DPT type vaccines may cause flare-ups and subsequent HO in individuals with FOP regardless of route of administration. Given these experiences, it is recommended that no DPT type vaccines be given to individuals with FOP.

Other immunizations given by the SubQ route have not been reported to cause flare-ups or HO in those with FOP. Specifically, there are no reported cases of flare-ups following subcutaneous immunization with the MMR or MMRV vaccines despite the fact that they contain live viruses.

In individuals with hemophilia, IM injections may cause hemorrhage. Because of this risk, the World Federation for Hemophilia recommends the SubQ route for all immunizations for individuals with hemophilia (Srivastava et al., 2020). It is standard practice at most Hemophilia Treatment Centers to recommend SubQ administration of all vaccines (Ragni et al., 2000; Ritchey, 2005; Carpenter et al., 2015; Schaefer et al., 2017). However, of the vaccines recommended for IM administration and given SubQ to hemophilia patients, to date only Hepatitis A (Ragni et al., 2000), Hepatitis B (Carpenter et al., 2015), and diphtheria-tetanus (Cook, 2008; Schaefer et al., 2017) vaccines have been shown to be effective in providing immunity. There are no published data regarding effectiveness of other IM vaccines given SubQ.

A concern for giving several vaccines SubQ has been granuloma formation at the injection site (Pembroke & Marten, 1979). These granulomas are considered to be the result of hypersensitivity to aluminum, an adjuvant to the other components of the vaccine. In a prospective cohort study in Sweden, Bergfors and associates reported that long lasting, intensely itching granulomas occurred in less than 1% of children receiving injections of DPT vaccines. The incidence of granulomas was similar whether the injections were given IM or SubQ (Bergfors et al., 2003 and 2014). Furthermore, granulomas have not been reported with SubQ vaccines administered to patients with hemophilia (Ritchey, 2005; J. Huang, personal communication). We are not aware of granuloma formation after any immunizations in individuals with FOP.

Based on the above information, it may seem reasonable to recommend that individuals with FOP receive all their recommended immunizations by SubQ injection. However, the situation is more complicated than that. Several of the routine vaccines are conjugated with components of either diphtheria or tetanus vaccines. Because the component(s) in DPT type vaccines that cause FOP flare-ups and HO have not been identified, it may be prudent for FOP patients to avoid vaccines that are conjugated with components of DPT vaccines (See Sections 4 and 5 below).

Recommendations for Immunization in FOP:

The following sections list vaccines recommended by the ACIP for routine immunization of individuals from birth to 18 years of age and for adults along with our cautions regarding administration to individuals with FOP. The median age of diagnosis of FOP is just under six years (Kitterman et al., 2005). Therefore, many vaccines will have already been administered IM by the time that the person has been diagnosed with FOP.

General Recommendation:

Do not give ANY immunizations to individuals with FOP during a flare- up. It would be preferable to wait 6 to 8 weeks after the flare-up has clinically resolved.

Recommendations Regarding Specific Vaccines:

1. Vaccines recommended by the ACIP to be given SubQ to all and appear to be safe for FOP patients: (These contain no components of diphtheria or tetanus.)

Measles, Mumps, Rubella Vaccine (MMR; brand names: M-M-R II, Priorix)

Varicella Vaccine (VAR; brand name: Varivax)

Measles, Mumps, Rubella, Varicella Vaccine (MMRV; brand name: ProQuad)

Inactivated Polio Vaccine (IPV; brand name: Ipol)

Pneumococcal 23-valent Polysaccharide Vaccine (PPSV23; brand name: Pneumovax-23)

2. Vaccines recommended by the ACIP to be given IM but are effective SubQ and are probably safe for FOP patients: (These contain no components of diphtheria or tetanus.)

Hepatitis A Vaccine (HepA; brand names: Havrix, VAQTA)

Hepatitis B Vaccine (HepB; brand names: Energix-B, Recombivax-HB, Heplisav-B)

3. Vaccines recommended by the ACIP to be given IM and are probably safe for FOP patients, but there are no data on their effectiveness when given SubQ: (These contain no components of diphtheria or tetanus.)

Meningococcal serogroup B Vaccine (MenB; brand names: Bexsero; Trumenba)

Human Papilloma Virus Vaccine (HPV; brand name:Gardisil-9)

Haemophilus influenzae type B vaccine (HiB: brand name: PedvaxHIB). Note that this is the only brand of HiB that is not conjugated to a component of diphtheria or tetanus.

4. Vaccines recommended by the ACIP to be given IM, but there are no data on their effectiveness when given SubQ, and these vaccines may NOT be safe for FOP patients because they are conjugated to a component of diphtheria or tetanus:

Haemophilus influenzae type B vaccine (HiB; brand names: Hiberix; Act HiB)

Meningococcal serogroups A, C, W, Y (brand names: Menactra; Menveo)

Pneumococcal 13-valent conjugate vaccine (PCV13; brand name: Prevnar-13)

Pneumococcal 15-valent conjugate vaccine (PCV15; brand name: Vaxneuvance)

HiB/MenC combination vaccine (brand names: Menitorix; Menhibrix)

5. Diphtheria, Pertussis, Tetanus type Vaccines:

These vaccines are not routinely recommended in FOP because of the experience that they may cause flare- ups, HO, and permanent loss of joint motion (Lanchoney et al., 1995; F. Kaplan, personal communication). Therefore, certain precautions should be taken to avoid or treat the diseases that these vaccines prevent.

However, there may be certain situations where the vaccine needs to be given to prevent life threatening illness (See Section C 4, below):

a. Diphtheria is a rare disease in the United States with less than 1 case per year in the past 20 years. If diphtheria is suspected clinically, follow the diagnosis and treatment guidelines of the CDC (https://www.cdc.gov/diphtheria/index.html) and the American Academy of Pediatrics (Kimberlin et al., 2021, Diphtheria) and consult with an infectious disease specialist.

b. Pertussis is a particular risk for infants and those with respiratory compromise (common in FOP). All household contacts of individuals with FOP should be immunized for pertussis. If there is a local outbreak of pertussis, those with FOP should not attend school during the outbreak. If pertussis is suspected in an individual with FOP, start early treatment with antibiotics as recommended by the CDC (https://www.cdc.gov/pertussis/) and the American Academy of Pediatrics (Kimberlin et al, 2021, Pertussis). If a household contact is diagnosed with pertussis, the individual with FOP should be given post-exposure prophylaxis.

c. Tetanus. In case of a wound considered a risk for tetanus, follow the guidelines for “Wound Management for Tetanus Prevention” of the CDC (https://www.cdc.gov/tetanus/index.html) and the American Academy of Pediatrics (Kimberlin et al, 2021, Tetanus). In addition, it is recommended that consultation be obtained with an infectious disease specialist. The use of Tetanus Immune Globulin (TIG) given subcutaneously should be considered for acute management.

Additional considerations about TIG for FOP include:

1. If TIG is to be given IM, the injection site should be chosen to be near joints or muscles that have already lost function. This may be a non-standard site. Thus, if a flare-up develops, it is less likely to worsen mobility significantly. Alternatively, TIG can be given SubQ, but the efficacy is unknown. However, recent data in immunocompromised patients show that immunoglobulins can be effectively delivered SubQ.

2. Because IM injection of TIG may precipitate a flare-up, give prophylactic prednisone 2 mg/kg/day (up to a maximum of 100 mg/day) for 2 days. Then taper the daily dose by 50% every other day. Note that this is shorter than the usual course for treatment of a flare-up, which is usually 4 days at 2 mg/kg/day. Prophylactic prednisone is recommended only with TIG and is not necessary for other immunizations.

3. Because the IM injection can cause significant inflammation, give ibuprofen immediately prior to the injection and continue with standard age/weight appropriate dosing for 7 days, even if no symptoms are present.

4. In the event that TIG is not available, and the only option is to use a Td containing vaccine, the Td vaccine should be given SubQ and the patient with FOP should be given prophylactic prednisone 2 mg/kg/day (up to a maximum of 100 mg/day) for 2 days. Then taper the daily prednisone dose by 50% every other day. Note that this is shorter than the usual course for treatment of a flare-up, which is usually 4 days at 2 mg/kg/day followed by a daily taper.

6. Rotavirus Vaccines (brand names: Rotarix, RotaTeq) are oral vaccines that contain live virus. The CDC recommends these vaccines for infants 2 to 6 months of age to prevent gastroenteritis caused by Rotavirus. Because the majority of those with FOP are not diagnosed until later in life, many with FOP will already have received one of these vaccines before FOP has been diagnosed.

7. Dengue Vaccine (brand name: Dengvaxia) is recommended only for children and adolescents 9- 16 years old who have laboratory-confirmed previous dengue virus infection and are living in an area where dengue is endemic.

8. Other Vaccines

a. Covid-19 Vaccines. See section on COVID vaccines

b. Cholera Vaccine (brand names: Dukoral; Shancol; Euvichol-Plus): These oral vaccines are recommended only for the following: (i) in areas where local transmission of cholera occurs; (ii) during humanitarian crises with a high risk of cholera; and (iii) during outbreaks of cholera. None of these vaccines are currently available in the United States. No data are available regarding these vaccines in FOP. (https://www.cdc.gov/cholera/vaccines.html)

c. Japanese Encephalitis Vaccine (JE-Vax; brand name: Ixiaro) is routinely given in several Asian countries where there is a high risk of this disease. This vaccine is given IM; there is no information regarding SubQ administration of Ixiaro. Because of the high rates of mortality and neurologic sequelae from Japanese Encephalitis, (Hills et al, 2019), individuals planning to visit Asia should discuss with their physician whether the protective effect of the vaccine outweighs the risk of flareups or HO from the IM administration of the vaccine.

d. Rabies Vaccine (brand names: Imovax; RabAvert) are cell culture vaccines that are recommended by the CDC and are administered on days 0, 3, 7, and 14 after exposure to Rabies (https://www.cdc.gov/vaccines/hcp/vis/vis-statements/rabies.html). Both vaccines can be given via the intradermal route which is as immunogenic and safe as IM (https://www.who.int/teams/control-of-neglected-tropical-diseases/rabies/vaccinations-and- immunization).

e. Tuberculosis: Bacille Calmette-Guerin (BCG) Vaccine is routinely given to infants to prevent tuberculosis in countries and areas where there is a high risk for the disease. Depending on the preparation, BCG can be given percutaneously with a multiple puncture device (https://www.fda.gov/downloads/biologicsbloodvaccines/vaccines/approvedproducts/ucm20 2934.pdf) or injected intradermally (Hawkridge et al., 2008).

f. Typhoid Fever vaccine (brand names: Typhim Vi; Vivotif): The World Health Organization (WHO) recommends immunization for protection against Typhoid Fever only for individuals in areas where there is a high risk for the disease. Typhim Vi is given IM for individuals >2 years of age; Vivotif is given orally for individuals >6 years of age. Individuals with FOP who plan to travel to areas where there is a high risk of Typhoid Fever should consult with their physician to decide whether the risk of Typhoid Fever is greater than the risk of the vaccine. Two other typhoid vaccines (Typbar Vi and Pedatyph) are conjugated to tetanus toxoid and should not be given to individuals with FOP.

g. Yellow Fever Vaccine (brand names: YF-VAX, Stamaril). YF-VAX is recommended for persons age 9 months and older who are traveling to or living in areas at risk for Yellow Fever transmission in South America and Africa. This vaccine is given SubQ. At this time there is limited availability of YF-VAX. Stamaril is not available in the United States.

h. Zoster Vaccines (brand names: Shingrix; Vostarax) The ACIP recommends Zoster Vaccine only for individuals 50 years of age and older to prevent Shingles (Herpes Zoster), which is due to reactivation of the Zoster-Varicella virus that causes Chickenpox. There are two vaccines available. Shingrix is a recombinant vaccine that contains no live virus. Vostarax is a live virus vaccine. For individuals with FOP 50 years of age and older, these vaccines should be given SubQ.

i. Respiratory Syncytial Virus (RSV). At this time there are two approved vaccines (Arexvy or Abrysvo) for RSV. Both vaccines are administered intramuscularly and should not be given to individuals with FOP.

References

Bergfors E, Hermansson G, Nystrom-Kronander U, Falk L, Valter L, Trollfors B. How common are long- lasting, intensely itching vaccination granulomas and contact allergy to aluminum induced by currently used pediatric vaccines? A prospective cohort study. Eur J Pediatr 173: 1297-1307, 2014

Bergfors E, Trollfors B, Inerot A. Unexpectedly high incidence of persistent itching nodules and delayed hypersensitivity to aluminium in children after the use of adsorbed vaccines from a single manufacturer. Vaccine 22: 64-69, 2003

Carpenter SL, Soucie JM, Presley RJ, Ragni MV, Wicklund BM, Silvey M, Davidson H. Hepatitis B vaccination is effective by subcutaneous route in children with bleeding disorders: a universal data collection database analysis. Haemophilia 21: e39-e43, 2015

Cook IF. Evidence based route of administration of vaccines. Hum Vaccin 26: 67-73, 2008

Hawkridge A, Hatherill M, Little F, Goetz MA, Barker L, Mahomed H, Sadoff J, Hanekom W, Gaiter L. Efficacy of percutaneous versus intradermal BCG in the prevention of tuberculosis in South African infants: randomized trial. BMJ 337:a2052, 2008

Hills SL, Walter EB, Atmar RL, Fischer M. Japanese encephalitis vaccine: recommendations of the Advisory Committee on immunization practices. MMWR 19:68:1-33, 2019

Kimberlin DW, et al. Red Book: 2021-2024 Report of the Committee on Infectious Diseases (32nd Ed). American Academy of Pediatrics. Diphtheria, pp 304-307; Pertussis, pp 578-589; Tetanus, pp 750-755, 2021

Kitterman JA, Kantanie S, Rocke DM, Kaplan FS. Iatrogenic harm caused by diagnostic errors in fibrodysplasia ossificans progressiva. Pediatrics 116: e654-e661, 2005

Lanchoney TF, Cohen RB, Rocke DM, Zasloff MA, Kaplan FS. Permanent heterotopic ossification at the injection site after diphtheria-tetanus-pertussis immunizations in children who have fibrodysplasia ossificans progressiva. J Pediatr 126: 762-764, 1995

Pembroke AC and Marten RH. Unusual cutaneous reactions following diphtheria and tetanus immunization. Clin Exp Dermatol 4: 345-348, 1979

Ragni MV, Lusher JM, Koerper MA, Manco-Johnson M, Krause DS. Safety and immunogenicity of subcutaneous hepatitis A vaccine in children with haemophilia. Haemophilia 6: 98-103, 2000

Ritchey AK. Administration of vaccines to infants and children with hemophilia. A survey of Region III comprehensive hemophilia treatment centers. Blood 106: 4079, 2005

Roush SW, Murphy TV, and the Vaccine-Preventable Disease Table Working Group. Historical comparisons of morbidity and mortality for vaccine-preventable diseases in the United States. JAMA 298: 2155-2163, 2007

Schaefer BA, Gruppo RA, Mullins ES, Tarango C: Subcutaneous diphtheria and tetanus vaccines in children with haemophilia: a pilot study and review of the literature. Haemophilia 23: 904-909, 2017

Srivastava A, et al. WFH Guidelines for the Management of Hemophilia, 3rd Ed. Haemophilia 26 Suppl 6: 1-158, 2020

5-8. Immunizations for Influenza in FOP

Influenza (“the flu”) is a major cause of morbidity and mortality worldwide. It is especially dangerous for those with FOP (Scarlett et al., 2004). Every year, flu vaccines are produced based on the predicted strains that will be prevalent in the following cycle. The Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC) recommend flu vaccinations by the end of October in the United States. Other countries may have different schedules and types/brands of vaccines available. Timing of the vaccinations should be determined with the local health care provider.

The most common forms of flu vaccinations are administered intramuscularly (IM) or provided as a live attenuated virus delivered in an intranasal form. In some years, transdermal and intradermal flu vaccines (given via a patch through the skin or injected just under the skin but not into the deeper tissues) may be available. Availability is based on manufacturing and effectiveness assessments that are performed yearly on that batch of vaccine.

Live attenuated flu vaccines are not recommended

The live attenuated intranasal form of the flu vaccine (such as Flumist® in the United States) has been reported to be associated with flares in some patients with FOP (F. Kaplan, Personal communication). This intranasal vaccine is not recommended for patients with FOP or their family members for this reason.

Transdermal or intradermal vaccines are preferred, when available

If transdermal or intradermal forms of the flu vaccine are available, we recommend, as we have for many years, using those routes. Information about the seasonal influenza flu vaccine in the United States can be found on the CDC website: https://www.cdc.gov/flu/vaccines/index.htm

Subcutaneous alternative route for flu vaccine administration

In years when the transdermal or intradermal forms are not available, we recommend that people living with FOP receive the flu vaccine using a modified protocol where the regular flu vaccine is given subcutaneously. Although there is no clear data as to how efficacious this is, prior studies suggest that there will be some efficacy despite being administered by a different route. Note that this will likely require a physician or physician’s office to administer the flu vaccine, as many places (i.e. pharmacies) will not deviate from their normal protocol of intramuscular injection.

For children, have one dose (typically 0.25 ml, depending on the formulation) of the intramuscular vaccine administered subcutaneously. Do not deliver the vaccine intramuscularly.

For adults, either have two doses of the pediatric dose (typically 0.25 ml each) intramuscular vaccine administered subcutaneously, at two different locations. Alternatively, have the regular adult dose (typically 0.5 ml, depending on the formulation) split and administered as two separate subcutaneous injections at two different locations. The locations do not need to be far apart. Injection of 0.5 ml subcutaneously in any location may be uncomfortable. The ICC does NOT recommend to take the vaccine intramuscularly.

Special precautions for vaccination of patients with FOP

For all vaccinations in persons living with FOP, it is recommended that:

An injection site be chosen near a joint or muscle group that has already been affected by HO, and in a location that would not cause complications if heterotopic bone was to form. That way, if a flare does develop, it is less likely to result in loss of mobility.

For all patients, it is recommended to take a dose of acetaminophen or ibuprofen with the vaccine to help with any discomfort that the vaccine may cause.

Vaccinations should not be given within 2 weeks of a flare or flare-like symptoms. It is advised to wait a minimum of 2 weeks but prefer 6-8 weeks because flareups can often occur in temporal clusters. This strategy is used to decrease the chances of a vaccine inducing a subsequent flare.

Family members living in the same home and caretakers should get the standard intramuscular flu vaccination on schedule. The nasal flu spray is NOT recommended for those in close contact with individuals living with FOP because the attenuated virus, though weaker, can still give a mild case of the flu to contacts.

Please keep in mind that those living with FOP should avoid ANY immunizations during an active flare-up – and for at least 6-8 weeks thereafter.

Antivirals – Oseltamivir/Tamiflu

If a person living with FOP or anyone living with or caregiving for a person with FOP develops symptoms suggestive of the flu, they should get prompt evaluation (including evaluation for other infections, such as COVID or RSV) and consider antiviral treatment (i.e. oseltamivir, Tamiflu®). Oseltamivir is only effective against influenza and does not work against the common cold or other viruses. The effectiveness of oseltamivir is highest in the early phase of an infection, so prompt medical attention is important when symptoms start (typically a combination of high fever and upper respiratory symptoms). Nasal swab testing may be needed to confirm infection with influenza. Oseltamivir does not have a long shelf life, so we generally recommend that a prescription be available “on hold” at a 24-hr pharmacy and that the medication be started once influenza infection has been confirmed by a medical care provider (Jefferson et al., 2014).

Infection Prevention for Everyone

Everyone should practice everyday preventive actions to stop the spread of germs as shared by the CDC on their website at https://www.cdc.gov/flu/protect/preventing.htm.

Try to avoid close contact with sick people.

While sick, limit contact with others as much as possible to keep from infecting them.

If you are sick with flu symptoms, CDC recommends that you stay home for at least 24 hours after your fever is gone except to get medical care or for other necessities. (Your fever should be gone for 24 hours without the use of a fever-reducing medicine).

Cover your nose and mouth with a tissue when you cough or sneeze. Throw the tissue in the trash after you use it.

Wash your hands often with soap and water. If soap and water are not available, use an alcohol-based hand rub.

Avoid touching your eyes, nose and mouth. Germs spread this way.

Clean and disinfect surfaces and objects that may be contaminated with germs like the flu.

See Everyday Preventive Actions and Nonpharmaceutical Interventions (NPIs) for more information about actions – apart from getting vaccinated and taking medicine – that people and communities can take to help slow the spread of illnesses like influenza (flu).

References

Jefferson T, Jones MA, Doshi P, Del Mar CB, Hama R, Thompson MJ, Spencer EA, Onakpoya I, Mahtani KR, Nunan D, Howick J, Heneghan CJ. Neuraminidase inhibitors for preventing and treating influenza in healthy adults and children. Cochrane Database Syst Rev 2014 Apr 10;(4)

Scarlett RF, Rocke DM, Kantanie S, Patel JB, Shore EM, Kaplan FS. Influenza-like viral illnesses and flare-ups of fibrodysplasia ossificans progressiva (FOP). Clin Orthop Rel Res 423: 275-279, 2004

5-9. Coronavirus (COVID-19) Precautions & Guidance for FOP Patients & Families

The Coronavirus (COVID-19) pandemic continues to pose a significant risk to the population worldwide with new variants of SARS-CoV-2 virus that are emerging. The ICC recommends that people living with FOP continue to follow precautionary measures to prevent infection from SARS-CoV-2, the virus that causes the COVID-19 illness.

The ICC is providing this update to the prior statement in May 2022. This document focuses on updated information reporting on COVID-19 infection and vaccination in FOP patients, approval on COVID-19 vaccination in children aged 6 months and above, as well as boosters and treatment.

The recommendations are changing rapidly and are country specific. Most countries have ended their emergency regulations for COVID-19.

The ICC does not provide recommendations on whether a patient with FOP should or should not receive a COVID vaccine.

The decision to take a vaccine is a personal one and based on the balance of risks and benefits, and this should be discussed with your medical team. ICC continues to recommend that COVID-19 vaccines be administered that same route that it was approved (i.e., intramuscular).

Additional information about COVID-19 and COVID vaccination in patients with FOP is now published. (https://ojrd.biomedcentral.com/articles/10.1186/s13023-022-02246-4 and https://ojrd.biomedcentral.com/articles/10.1186/s13023-023-02638-0)

Amongst 23 FOP patients who received intramuscular COVID-19 vaccination. Most common symptoms were pain/soreness, tiredness and swelling. These symptoms are similar to those reported by the general population. One out of 23 developed a flare-up. No patients who received the COVID-19 vaccine were hospitalized.

Amongst 19 FOP patients with COVID-19 infection. Most common symptoms were fatigue, loss of taste or smell and cough. Two out 19 FOP patient developed flare ups and 3 patients were hospitalized.

Vaccines are now generally available for children age 6 months or over. ICC does not provide recommendations on whether a patient with FOP should or should not receive a COVID vaccine. Discuss with your medical team, as local recommendations on when to take a vaccine or eligibility for a vaccine may vary.

ICC does not provide recommendations for or against the booster vaccination, but boosters should be considered if you completed vaccinations previously and are in a high risk area. Please consult with your medical team prior to receiving the booster to discuss if a booster is appropriate and safe.

Patients with FOP are at high risk of complications with COVID-19 infection and should discuss with their medical team if use of monoclonal antibodies or anti-retroviral medications would be beneficial, in the event of a SARS-CoV2 infection.

Monoclonal antibodies are given intravenously and are approved for adults and pediatric patients (≥12 years of age weighing ≥40 kg). Those interventions should be started as early as possible and before 10 days of symptoms onset. Note that some monoclonal antibodies are not effective against the newest strains of SARS-CoV2.

Anti-retrovirals are pills that have been approved. These should generally be administered within 5 days of symptoms onset.

Availability and recommendations of the use of these treatments are rapidly changing and country specific. Some of these therapies may not work against strains prevalent in a particular region. Please consult with your local medical team for recommendations

Discuss with your doctors to make sure there are no medication interactions

If you are in a clinical trial, it is important to discuss any vaccines or therapies with your study doctors.

Clinical data about FOP and COVID/SARS-CoV2 infections are published here:

Social and clinical impact of COVID-19 on patients with fibrodysplasia ossificans progressiva | Orphanet Journal of Rare Diseases | Full Text (biomedcentral.com)

https://ojrd.biomedcentral.com/articles/10.1186/s13023-022-02246-4

A follow-up report on the published paper Social and clinical impact of COVID-19 on patients with fibrodysplasia ossificans progressive (biomedcentral.com)

https://ojrd.biomedcentral.com/articles/10.1186/s13023-023-02638-0

Masking continues to be an important component of controlling the spread of SARS-CoV-2. The ICC strongly recommends the use of tight fitting N95, KN95, or KF94 masks whenever possible to protect the wearer from infection by SARS-CoV-2. If these masks are not available or uncomfortable, then wearing a 3-layer surgical mask would be the next best choice.

The ICC is aware of a recent publication suggesting that the use of subcutaneous injection of the vaccine could still induce adequate vaccine response. However, this study likely delivered the vaccine via a shallow intramuscular route. Furthermore, there are multiple reports in the literature of severe reactions to subcutaneous injection of the COVID vaccine. Efficacy of subcutaneous delivery of a COVID vaccine remains unproven. Therefore, the ICC continues to recommend following the manufacturers’ directions for vaccination and NOT taking intramuscular COVID vaccines by the subcutaneous route.

If you decide to take the COVID vaccine or booster, we recommend:

Discuss your plans with your doctor. Review any potential allergies or prior reactions like anaphylaxis that you should consider before taking the vaccine.

If you are in a clinical trial or study, it is important to discuss any vaccines or therapies with your study doctors.

Take the vaccine via the recommended route and dose (i.e., intramuscular (IM) for the currently available vaccines). Safety and efficacy of taking an IM vaccine through the subcutaneous route is not known and could cause a more unexpected inflammatory responses or poor immune reactions and is currently not recommended.

If possible, take the vaccine in a location that is already fused, as the vaccines all appear to induce some local site reaction (arm pain and swelling). For example, if your left hip or right shoulder are fused, you should use the muscle around those sites.

As with other vaccines, patients with FOP should be flare free for at least 2 weeks prior to receiving the vaccine.

Have the injection done by an experienced nurse, physician, or pharmacist.

Use the shortest needle available (this varies with clinical site). The clinician should be aware that patients with FOP may have hidden HO and thinned muscle at the site of the injection. Avoid injecting directly next to existing HO bone if possible.

Prior to the vaccination, have ibuprofen or acetaminophen available. Also, have a course of prednisone for flares available.

The symptoms reported by patients with FOP after a COVID vaccination are similar to those reported for the general population (low grade fever, headache, muscle aches, fatigue, etc.).

Make sure your physician is familiar with the ICC Treatment guidelines, specifically on vaccinations and flare management (see below). Notify your physician you plan to do the vaccine, and when.

On the day of the injection:

Your local team may not allow you to take ibuprofen or acetaminophen prior to the injection (this is because they may screen for COVID symptoms first).

After you receive your injection, there may be a brief observation period.

After that is completed, take ibuprofen (2 to 3 times/day) or acetaminophen (2-3 times/day) following the label instructions, for the next 48 hrs, regardless of your symptoms.

Rest and stay hydrated.

In the event of a flare, contact your physician for guidance. You may need to do a short course of prednisone, but this needs to be balanced with the immunosuppressive effects of steroids. The usual flare dosing is prednisone 2 mg/kg/day up to 100 mg, for 4 days; your physician may recommend starting at a lower dose, depending on your symptoms.

Even if you take the vaccine, you still need to continue physical distancing, wearing masks, and appropriate hand washing

The ICC can’t guarantee that these steps will “work” to prevent complications. Flare or flare-like activity has been reported in patients with FOP who receive a COVID vaccine. All medications and treatments have risk, so it is important to discuss your specific situation with your doctor as you decide whether the vaccine is appropriate for your situation.

Make sure that you complete the full immunization regimen recommended (i.e., do both doses if the vaccine recommends 2 doses)

Discuss with your physician if you should do a booster and if that is appropriate for you, such as to cover local SARS-CoV2 variants. This is an area of active investigation so will need to be updated as the ICC receives more information.

How does the development of a vaccine change things?

The development and distribution of vaccines have had a major impact on the COVID pandemic.

Vaccine outcomes and the emergence of variants are areas of intense ongoing study worldwide, and the field continues to rapidly evolve.

The duration of immunity conferred by the vaccines is unknown but does not seem to be lifelong.

The ICC recommends that FOP family members and caregivers be fully vaccinated for SARS-CoV2 if safely available for them.

Vaccinations can take 2+ weeks to show any efficacy, so there is no protection immediately after vaccination. In addition, vaccines do not confer absolute immunity to the SARS-CoV-2 virus, and may not have activity against all forms of the SARS-CoV-2 virus.

Anyone who receives a vaccine should still continue with masking, hand hygiene, and physical distancing.

Please discuss with your local care providers regarding benefits and risk of any locally approved vaccines and boosters.

It’s very important to maintain social distancing and wearing a mask when around members outside your household

Recommendations if a patient with FOP or caregiver tests positive for SARS-CoV2

Notify your primary care physician to help coordinate care.

Follow your local guidelines for isolation/quarantine and the needed durations and procedures. Everyone, including the person with the positive SARS-CoV2, should wear a mask at all times to avoid transmission.

Patients who are negative for SARS-CoV2 but have similar symptoms should be tested for influenza.

Patients with FOP are at high risk of complications with COVID-19 infection and should discuss with their medical team if use of monoclonal antibodies or anti-retroviral medications would be beneficial, in the event of a SARS-CoV-2 infection. The main reason for treatment would be to reduce respiratory complications, as patients with FOP are at high risk of breathing complications and are difficult to intubate. However, access to these medications may be limited in your area. Please discuss with your physician if these medications are an option and appropriate for you.

Monoclonal antibodies are given intravenously and are approved for adults and pediatric patients (≥12 years of age weighing ≥40 kg). Those interventions should be started as early as possible and before 10 days of symptoms onset.

Anti-retrovirals are pills that have been approved for treatment of COVID-19. These should generally be administered within 5 days of symptoms onset.

Availability and recommendations of the use of these treatments are rapidly changing and country specific. Please consult with your local medical team.

Discuss with your physician about any potential medication interactions prior to starting anti-viral therapies

References

Kou S, Kile S, Kambampati SS, Brady EC, Wallace H, De Sousa CM, Cheung K, Dickey L, Wentworth KL, Hsiao EC. Social and clinical impact of COVID-19 on patients with fibrodysplasia ossificans progressiva. Orphanet J Rare Dis 2022 Mar 4;17(1):107

Wallace H, Lee RH, Hsiao EC. A follow-up report on the published paper Social and clinical impact of COVID-19 on patients with fibrodysplasia ossificans progressiva. Orphanet J Rare Dis 2023 Mar 20;18(1):61

5-10. Acute & Chronic Pain Management in FOP

General Considerations

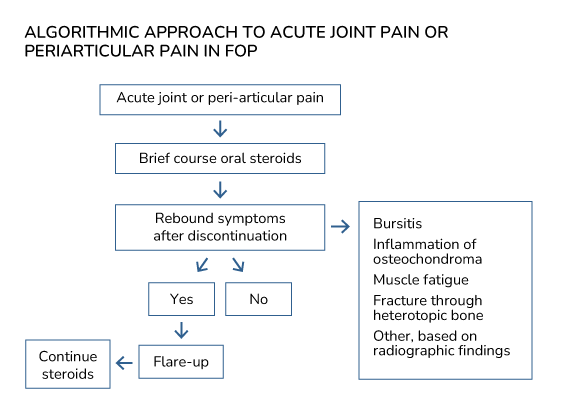

According to the IFOPA Patient Registry (Mantick et al., 2018), almost 90% of individuals with FOP have pain complaints. Major causes of acute pain in FOP are musculoskeletal in origin and include flare-ups, transient bursitis, inflammation of osteochondromas, muscle fatigue, and fracture through heterotopic bone.

The most important aspect of acute pain management is distinguishing acute pain due to flare-ups versus other etiologies. In a study on the natural history of flare-ups in FOP (Pignolo et al, 2016), the most painful flare-ups occur in the hips and knees. Quantitative sensory testing of patients with FOP revealed significant heat and mechanical pain hypersensitivity, suggesting a novel neuropathic pain phenotype (Yu et al., 2023).

Based on a recent evaluation of clinical and radiographic findings of acute hip pain in FOP (Kaplan et al., 2018; see section on Differential diagnosis of hip pain), an algorithmic approach to acute joint or periarticular pain may be proposed (Figure). After an initial brief course of steroids to empirically treat for a possible flare-up, observation for rebound symptoms with discontinuation is the critical node for further treatment decisions. The absence of rebound symptoms (i.e., resolution of pain complaints) suggests that the etiology for pain is not related to a flare-up. The presence of continued or worsening symptoms after discontinuation, however, strongly suggests a flare-up as the likely cause. Plain radiographs of the involved joint can be helpful in the management of acute periarticular pain.

Common causes of chronic pain in FOP include neuropathies, arthritis, generalized chronic pain syndrome in advanced FOP, and other causes of pain such as gastrointestinal pain (see section on gastrointestinal issues). The approach to chronic pain relies on distinguishing between neuropathic and nociceptive etiologies. Neuropathic pain results from damage to or pathology within the nervous system and can be central or peripheral. In FOP, neuropathies are the major cause of neuropathic pain, related to entrapment syndromes and/or nerve damage, and may be caused by peripheral or central nervous system phenomena intrinsically related to the cause of FOP (Kan et al., 2011; Kan et al., 2012; Peng et al., 2021; Yu et al, 2023). Nociceptive pain is caused by stimuli that threaten or provoke actual tissue damage. In FOP, the major causes of nociceptive pain are musculoskeletal pain (e.g., back pain, myofascial pain syndrome, ankle pain), inflammatory pain, and pain due to mechanical/compressive causes (e.g., visceral pain from expanding HO).

General principles of pain management should be applied to the treatment of chronic pain in FOP. The best approach is to target the etiology of the pain, whenever known, and to make reasonable attempts at understanding at least the type of pain when the etiology is unknown. Optimal outcomes often result from multiple approaches utilized in concert, coordinated via a multidisciplinary team. Some adjuvant, non- pharmacologic modalities can be effective in pain management. Finally, treatment of depression may provide pain relief separate from correction of the mood disorder.

Treatment of chronic pain is based on neuropathic versus nociceptive components. There is consensus among guidelines on pain management of non-FOP pain syndromes that first-line agents for neuropathic pain include either calcium channel alpha 2-delta ligands (e.g., gabapentin or pregabalin) or tricyclic antidepressants (Gilron et al., 2015; Finnerup et al., 2015). Serotonin norepinephrine uptake inhibitors (SNRIs) are identified as either first or second-line agents (e.g., duloxetine, venlafaxine), although they may be preferred to tricyclic antidepressants. Among the tricyclic antidepressants, side effect profiles appear to favor the secondary amine tricyclics (e.g., nortriptyline and desipramine), although the efficacy is the same for other tricyclics such as amitriptyline. Combination therapy is often required, because less than half of patients with neuropathic pain will respond to a single agent. However, evidence is scant regarding the efficacy and safety of combination treatment. Other second-line agents that may be used include tramadol and other antiepileptics (e.g., carbamazepine or oxcarbazepine). Opioids should be considered a third-line option in FOP, both because of abuse potential and the fact that activation of mast cells and the systemic release of histamine are common side effects of opioids, especially codeine and meperidine (Blunk et al., 2004). Topical agents can be used as adjunctive therapy as appropriate.

The pharmacologic approach to nociceptive pain first begins with an evaluation of risk factors that may contraindicate, limit, or otherwise call attention to the possibility of potential side effects related to the use of non-steroidal anti-inflammatory agents (NSAIDS), the mainstay of treatment (McCormack, 1994; Roelofs et al., 2008). Risk factors include advanced age, renal, hepatic, cardiovascular disease or risk, peptic ulcer, and glucocorticoid use. The latter is directly applicable to FOP, and systemic NSAIDS should not be used concomitantly with steroids. After risk factor evaluation, the next step to nociceptive pain management is an assessment of pain level. Mild to moderate pain can initially be treated with topical agents (see section on Topical Agents) and/or acetaminophen/paracetamol.

Pain not controlled by topical agents or acetaminophen/paracetamol should be managed with NSAIDs plus a proton-pump inhibitor or COX-2 inhibitor with or without acetaminophen/paracetamol. There is controversy over the maximal safe daily dose of acetaminophen, but a 3g to 3.25g daily dose appears to be within a safe maximal range (Heard et al., 2007).

Treatment of moderately severe to severe pain without an inflammatory component or with risk factors for NSAID use should begin with acetaminophen/paracetamol and advanced to tricyclic antidepressants if pain is not adequately controlled. Moderately severe to severe pain with an inflammatory component should be initially treated with NSAIDs plus a proton-pump inhibitor or COX-2 inhibitor with or without acetaminophen/paracetamol. Use of COX-2 inhibitors may decrease the likelihood of gastrointestinal toxicity from NSAIDs (Silverstein et al., 2000). Tricyclic antidepressants can also be used if pain is not adequately controlled. The addition of baclofen or other muscle relaxant may be appropriate for a short period of time if there is a spasmodic component to the pain (see section on Muscle Relaxants). For the reasons stated above, opioids should also be considered a third-line option in FOP for the management of nociceptive pain.

There are many causes of acute and chronic pain in FOP, and each individual must be carefully evaluated before effective treatment can be planned and implemented (Kaplan et al., 2008). Many FOP flare-ups, especially those around the hips and knees, are extremely painful and may require a brief course of well-monitored narcotic analgesia in addition to the use of non-steroidal anti-inflammatory medications, COX-2 inhibitors, and/or oral or IV glucocorticoids. Other types of transient pain syndromes may be caused by neuropathies resulting from acute flare-ups, transient bursitis, inflammation of osteochondromas, arthritis and muscle fatigue, to mention only a few.

To date, much remains unknown regarding the dynamics of pain and emotional health in FOP during flare- up and also quiescent, non-flare-up disease phases. In order to elucidate the occurrence and effect of pain in FOP, a study analyzed patient-reported outcomes measurement information system-based questionnaires completed by 99 patients participating in the international FOP Registry over a 30-month period (Peng et al., 2019). The study observed that while moderate to severe pain (≥4, 0-10 pain scale) was commonly associated with flare-ups (56-67%), surprisingly, 30-55% of patients experienced similar pain levels during non-flare-up states. Furthermore, independent of the flare-up status, the severity of pain in FOP patients was found to be inversely correlated with emotional health, physical health and overall quality-of-life. These findings strongly suggest the need for an improved understanding of pain and emotional health in FOP during flare-up and quiescent periods (Peng et al., 2019).

Those with chronic pain of diffuse musculoskeletal origin may require more specialized pain management programs directed by pain management specialists. Attempts should be made to minimize chronic discomfort and maximize physical and cognitive function. In most cases, narcotic agents should be avoided to minimize the risk of dependency on these agents. While some may require chronic narcotic analgesics late in the course of their disease process, attempts should be made to monitor this carefully to avoid constipation and respiratory suppression.

Use of alternative of complementary therapies have not been well investigated but may provide options for reducing systemic pain medication use. Pain neuroscience education may be useful and has been shown to be an effective intervention in all types of pain (Louw et al., 2016). Acupuncture is not recommended due to the potential for tissue trauma.

Other complementary or integrative medicine techniques for pain management should be considered, including the use of biofeedback, therapy pools, therapeutic relaxation, auto-hypnosis, cognitive behavioral therapy, gentle massage/acupressure, and medicinal marijuana (where available). These therapies should be discussed with the treating physician to ensure that there are no adverse interactions with other medications or therapies, or contraindications for an individual patient. Also, procedures such as acupressure and gentle massage need to be performed in a way that does not increase the risks of trauma or inducing a flare. Please discuss with the primary care physician or local pain management team for referrals to a reputable complementary or integrative medicine practitioner.

For those with more chronic pain management issues, a consultation with a pain management specialist may be helpful and is recommended.

Medical Cannabis